Throughout the 1990s and into the early 2000s, rural communities were rocked by shockwaves of mad cow disease, salmonella in eggs, international outbreaks of avian flu in poultry farming, and the terrible circumstance of tens of thousands of farm animals being burnt on pyres to curb the spread of Foot and Mouth Disease in lieu of a coherent national vaccination policy. Television screens brought the reality of tackling virulent animal disease forcefully into our living rooms. Sustain and our members spent the next decade and more working on projects to help raise standards for British food, farming and fishing, and secure better livelihoods for sustainable farmers and fishers, at home and abroad. Over many years of practice and development, food buying standards for the public sector, significant investment in rural infrastructure, and an upsurge of interest in local and traceable food were just some of the more positive outcomes from that period.

A memorable phrase of those tumultuous times was that British farming was “on its knees” and needed concerted action to be “put back on its feet”. After such major disruption, the food and farming industries and commentators frequently spoke of the need to “rebuild trust” in the food system, and for people to “know where our food comes from”. People and animals lost their lives; farmers their stock and their livelihoods; some decision-makers their jobs. Our green and pleasant countryside was covered in smoke. A National Audit Office report in 2002 showed that the Foot and Mouth outbreak had cost the public sector over £3 billion and the private sector more than £5 billion in lost jobs, income and tourism; the BSE outbreak perhaps another £4 billion. It has taken 15 years for the UK egg industry and Food Standards Agency, as well as millions of pounds of investment, to be able to declare – only at the end of last year – that is safe to eat soft-boiled British eggs, now reliably free of salmonella.

Fifteen or so years later, and here we are facing another major disruption to our our systems for food, farming and fishing, and for our countryside and rural communtiies - arguably much more significant, and probably with some similarly eye-watering price tags. This time it is Brexit.

Back in 2000 the newly created Defra set up a Food and Farming Commission, popularly known as the Curry Commission because of its Chair Sir Don Curry (now Lord Curry of Kirkharle, who spoke about that period at Sustain’s Annual Gathering in January 2017). The Curry Commission convened, took evidence and listened. It acted as an honest broker for many voices and concerns, from across industry, policy, environmental and health organisations. Most importantly, it sketched out the problems but moved swiftly to focusing on the positive – solutions to the crisis facing beleaguered farmers and rural economies. What could be done to put British farming back on its feet? The Curry Commission’s report is worth a re-read. It could (almost) have been written yesterday.

In November 2017, a new independent Food, Farming and Countryside Commission was launched, hosted by the RSA and funded charitably by the Esmée Fairbairn Foundation. Sustain’s Chief Executive Kath Dalmeny is one of 15 Commissioners, with Sir Ian Cheshire as the Chair and Director Sue Pritchard. It aims to provide the crucible for good ideas to come forward, to cultivate a national conversation and a mandate for a better approach to food, farming and the countryside.

In the midst of our current Brexit-fuelled major disruption, the challenges and themes feel oh-so familiar. However the scale, urgency and importance of the issues are far greater than before. More encouragingly, also far greater are the available science, examples of better practice and solutions. Fifteen years on, we know much more about how land management could be better for farmers, citizens, animals, wildlife, soil, water, pollinators and the wider environment – including climate change – itself far higher up the agenda than it was 15 years ago. We do not need to rehearse the problems. We need to move swiftly to convening around the solutions, and hence to the much more challenging question of how we will create the political and public mandate, and the momentum, to ensure that solutions are prioritised, embedded and rewarded in perpetuity.

No small task. But we must step up to the opportunities this moment in history presents. In the Sustain alliance, we’re calling this shift in mood and emphasis the Campaign for a Better Food Britain, and also the opportunity to instigate a beneficial race to the top. For the Food, Farming and Countryside Commission, it is a focus on solutions.

“Most importantly, we urgently need to ask ourselves: what kind of country do we want to be, and what do we, as citizens, really want from our food, farming and countryside?”

Sue Pritchard, Director, RSA Food, Farming and Countryside Commission

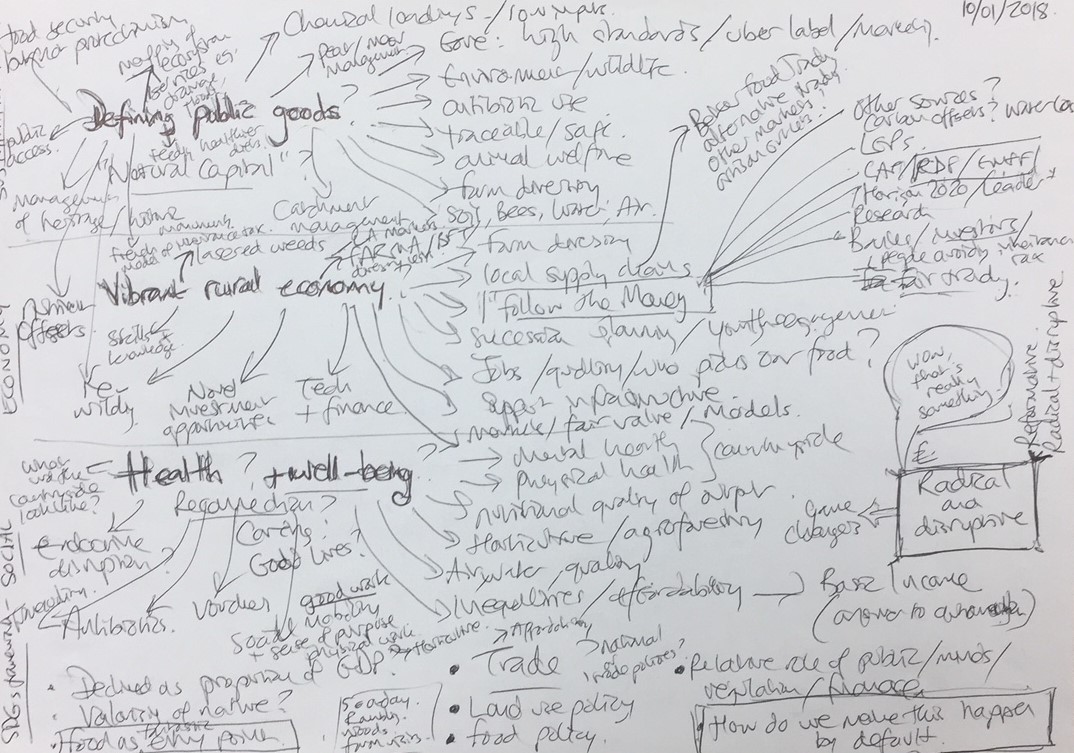

The first meeting of the Food, Farming and Countryside Commission took place in January 2018. My notes (snapshot above) reveal a veritable torrent of ideas, connections and enthusiasm. It really is a remarkable group of people. Our remit is very wide, and the sense of responsibility great. Nothing is yet set in stone, but I venture the following notes – reflecting both the early discussions and my own reactions – capturing a sense of some themes already emerging – important both to the Commission and to wider public debate and policy development:

- When we talk about ‘public money for public goods’, what do we mean by public goods?

- How can we support good livelihoods in farming, land use and thriving rural economies?

- How can we create a food, farming and countryside system that generates health and well-being?

And importantly, as one of my fellow Commissioners aptly put it, “How do we ensure that the beneficial stuff will in future happen by default?”

On public goods…

With the prospect of European money being liberated for domestic priorities, many are coming forward with new ideas for investing public money in sustainable farming and land use, to reward practices that the market does not pay for. Protection of natural systems – soil, pollinators, air quality, trees and agro-forestry, clean water, good drainage, flood protection and carbon sequestration, to name but a few; as well as wildlife, re-wilding of some areas, and creation and maintenance of beautiful landscapes and heritage features. Investment in whole-farm systems that cultivate fertility and natural resilience to disease, rather than rely on high levels of nitrogen fertilisers, pesticides and farm antibiotics. Good working conditions for the humans and good welfare for the animals throughout. Public money can help shift farming and land-use practices; make sustainable practices the norm.

With the prospect of European money being liberated for domestic priorities, many are coming forward with new ideas for investing public money in sustainable farming and land use, to reward practices that the market does not pay for. Protection of natural systems – soil, pollinators, air quality, trees and agro-forestry, clean water, good drainage, flood protection and carbon sequestration, to name but a few; as well as wildlife, re-wilding of some areas, and creation and maintenance of beautiful landscapes and heritage features. Investment in whole-farm systems that cultivate fertility and natural resilience to disease, rather than rely on high levels of nitrogen fertilisers, pesticides and farm antibiotics. Good working conditions for the humans and good welfare for the animals throughout. Public money can help shift farming and land-use practices; make sustainable practices the norm.

On rural economy…

We all need a much better appreciation of the importance of money being spread more fairly and sensibly in food, farming and rural development. Consumers need wholesome, affordable food; farmers, land managers and farm workers need decent livelihoods; and rural businesses need enough money to invest in change. It’s a vital and revitalising balancing act.

We all need a much better appreciation of the importance of money being spread more fairly and sensibly in food, farming and rural development. Consumers need wholesome, affordable food; farmers, land managers and farm workers need decent livelihoods; and rural businesses need enough money to invest in change. It’s a vital and revitalising balancing act.

A big theme should therefore be to “follow the money”. Here I will improvise much further than my meeting notes suggest:

- Re-allocation of CAP payments to “public money for public goods” – lots of groups are understandably focusing on this, the stakes and opportunities are high. The RSPB has done useful work on what it would actually cost to invest in restoring nature. The concept of ‘Natural Capital’ has gained traction over recent years, as has True Cost Accounting. Which approaches could help us towards a more beneficial with nature? Are there any pitfalls? A more sensible definition of farm productivity might also help.

- Other big strands of relevant money previously channelled wholly or partially via EU programmes. Examples include:

- European Agricultural Guarantee Fund (EAGF)

- European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development (EAFRD) – both these two cover the whole farm package including direct payments and, crucially, rural development funds

- European Regional Development Fund, which has previously been a source of investment in economically disadvantaged, often rural areas

- Leader+, an EU funding programme to revitalise rural areas and create jobs

- Horizon 2020 and other thematic funding programmes, which often have a sustainability strand

- The European Maritime and Fisheries Fund, which has recently provided large amounts of money to coastal communities, often to help them make the transition to more sustainable fishing gear and fishing practices

- Lots of research grants and government-backed industry R&D funds

Such public funds will be cherished – perhaps fought over – by politicians as a source of money to achieve manifesto commitments or to plug other funding gaps. The replacement for CAP money will sit with Defra. Rumours are appearing that other funding strands may be lumped together in a new ‘Prosperity Fund’ and perhaps housed with the Department for Communities and Local Government. Questions then arise about priorities, accountability and governance. Will such funds be subject to priorities such as achievement of climate change mitigation and adaptation? Will such funds, in their return to domestic policy-making, be invested in sustainable farming and rural economies? Or siphoned off for other purposes such as infrastructure development and housing? The Common Agricultural Policy billions often get discussed; the other funds rarely get air-time. We need to examine what good work such money could do, to get us to a better place.

And then there are lots of other ways that money flows to and from the rural economy, sometimes meeting bottle-necks for food, farming and countryside:

Local Enterprise Partnerships are interesting. Back in the time of the Curry Commission, Regional Development Agencies (RDAs) were a channel for substantial public money invested in the local infrastructure that helped a diversity of rural businesses – size, type and ambition – to flourish. Most offered support for food and farming businesses – the biggest employers in Britain - to thrive, through a mixture of business advice, start-up support, incubation, infrastructure and routes to market. The RDAs are long gone, replaced by Local Enterprise Partnerships, whose priorities are decided locally and who may consider food, farming and rural communities a priority, but then again may not. Could these once again be encouraged, or required, to run food, farming and rural development investment strands?

Local Enterprise Partnerships are interesting. Back in the time of the Curry Commission, Regional Development Agencies (RDAs) were a channel for substantial public money invested in the local infrastructure that helped a diversity of rural businesses – size, type and ambition – to flourish. Most offered support for food and farming businesses – the biggest employers in Britain - to thrive, through a mixture of business advice, start-up support, incubation, infrastructure and routes to market. The RDAs are long gone, replaced by Local Enterprise Partnerships, whose priorities are decided locally and who may consider food, farming and rural communities a priority, but then again may not. Could these once again be encouraged, or required, to run food, farming and rural development investment strands?- Banks and investors – what would it look like if these were more sustainable-farmer-friendly? Some banks like Triodos have a policy of lending only to farmers adopting sustainable practices such as organic, and enterprises that return more value than just money to their communities. Investors worth trillions are increasingly seeing farm practices such as profligate use of antibiotics as an investment risk. Could bank and investor money work harder to accelerate the transition to sustainable farming and land use? It would have to be patient and principled money. Such conversations should be provoked and listened to.

- Money also flows to farming and rural economies from trading, but not enough of it. If, as seems likely, public subsidies to farmers and land managers may taper out over time, how can we ensure that the market rises to the task of returning sufficient value to them, to provide a good livelihood, as well as sufficient surplus to be able to reinvest in better practices? This is why Sustain is campaigning for extension of the Grocery Code Adjudicator, as one small contribution to protecting farmers from unfair trading practices and hence make farm incomes more secure. But I’d go further and suggest we need to cultivate values-driven retailers and foodservice companies, supported by transparency and national policies to promote better farmgate prices that cover the cost of sustainable production. We have a lot to learn from values-driven pioneers such as Better Food Traders and other socially minded enterprises. Funding, policy and regulation can play a part in moving the market in a better direction.

- Land, tax and inheritance – all big and politically sticky themes that deserve attention. Land value and hence prospects for resilient rural economies, a thriving tourism industry, new entrants into farming and first-time house-buyers are profoundly affected by public policy on land, tax and inheritance. What are the new big ideas for dealing with such issues? How do other countries deal with this, and with what beneficial or detrimental outcomes? Such conversations are as old as the hills, but they need to be brought to the forefront once again.

- And then, more creative thinking about potential new money flows and responsibilities. Water companies are in the frame to cover some of the costs of clean water and flood prevention. Some also advocate farmers and land managers trading their carbon sequestration potential, offering soil improvement and tree-planting for carbon offset payments from other industries.

On health and well-being…

The connection between agricultural and land-use policy and health is not well-established, but is increasingly well understood. Our physical and mental health are deeply affected by the food we eat, our connection with nature, our connection to others, and the work that we do. It makes perfect sense to me, and many of the colleagues who move in our circles – nicely sketched out in this recent blog by Jo Lewis of the Food for Life programme. But I sometimes see furrowed brows when trying to explore this with a wider audience, especially those used to thinking narrowly about farm subsidies and rural economics.

The connection between agricultural and land-use policy and health is not well-established, but is increasingly well understood. Our physical and mental health are deeply affected by the food we eat, our connection with nature, our connection to others, and the work that we do. It makes perfect sense to me, and many of the colleagues who move in our circles – nicely sketched out in this recent blog by Jo Lewis of the Food for Life programme. But I sometimes see furrowed brows when trying to explore this with a wider audience, especially those used to thinking narrowly about farm subsidies and rural economics.

Water pollution, pesticide residues and endocrine-disrupting chemicals are clear illustrations of where farm policy, and the subsidies and rules that incentivise certain behaviours, have a direct link to human health. Farm antibiotic use has a direct link to the emergence of anti-microbial resistance and superbugs directly affecting people. We could do much more to reduce the burden of disease from such sources. Good regulation will be essential.

Perhaps more challenging to grasp is the idea of actively prioritising establishment of horticulture, especially in peri-urban areas, providing both good jobs, fresh food and opportunities to get involved closer to where most people live. We have made great progress in London and other pioneering cities such as Brighton & Hove and Bristol, supporting the creation of thousands of new community gardens - among them, a good number of peri-urban farms and commercial horticulture enterprises. How will more of us get to our five-a-day (or even 10-a-day) if we don't know and care about the source of our apples and salad leaves? We're talking about a shift in culture and values, not just a numerical target.

So here I am beginning to turn to the more emotional language of connection and values. Let's go there. How do we want to live our lives? And how can we use food and farming as the entry point? The narrative perhaps needs better story-tellers and perhaps even poets, but some topline thoughts are that we are talking about culture, and also about how planning policy, farming and rural development policy and investment can help shift culture for the better.

So, let us stroll together among some thoughts on how to cultivate a food, farming and countryside system that also cultivates human well-being:

We thrive when we have a chance to connect with nature. Many scientific studies have confirmed, but our hearts, GPs and therapists already knew – wilderness, mountains, moorlands, parks and green spaces, wildlife-friendly gardening and human-scale horticulture represent softening and beneficial aspects of our physical and mental landscape that can provide – yes, healthy nutrients – but also places to have those treasured unexpected conversations, memories and private moments; and places to let our over-taxed and anxious brains roam free.

We thrive when we have a chance to connect with nature. Many scientific studies have confirmed, but our hearts, GPs and therapists already knew – wilderness, mountains, moorlands, parks and green spaces, wildlife-friendly gardening and human-scale horticulture represent softening and beneficial aspects of our physical and mental landscape that can provide – yes, healthy nutrients – but also places to have those treasured unexpected conversations, memories and private moments; and places to let our over-taxed and anxious brains roam free.

We thrive when we can eat well. We eat the food we are presented with, we shop in the ways open to us, and what we learn from our childhood and family traditions shapes our diets, preferences, food values, transport choices, holiday destinations and long-term health. We have a better chance of good health if we can – for at least some of our meals – cook from fresh, incorporate fruit and vegetables and walk to enjoyable and sociable shopping outlets as part of our everyday lives. People who learn and love to cook and shop can eat more sociably and healthily. Those who live near markets and diverse food retail outlets value them for their food quality and social interaction. It’s not nostalgia, and it can be affordable to diverse communities. Yes, it's not for everybody, but the majority of the world still eats this way. Our modern disconnection is not the norm. Urban markets and rural market towns are a part of the fabric of good food infrastructure that keep farmers and rural communities connected with their customers, and citizens connected with their food.

It doesn’t have to be like this, and it won’t be fixed by ever cheaper low-quality food, nor by expecting farmers and the land to produce ever more for less. Sustain is currently working with Church Action on Poverty and communities up and down the country to develop positive community responses to food crisis and food deprivation. We are also convening specialists to talk about the policies that can fix the problems ‘upstream’, making good food affordable – not just cheap - returning decent livelihoods to food producers and decent food to people. This is the balancing act that breeds system-wide well-being.

The National Living Wage was a decent step in the right direction. Controlling housing and utility costs all help. Services such as meals on wheels for elderly and housebound people need to be protected and reinstated. A guaranteed basic income is starting to be discussed. Ensuring that the cost and value of food get more fairly distributed must also be part of the picture - we should remind ourselves that many farmers, as well as low-income consumers, experience poverty. The market needs regulating to deliver public goods.

Fixing these entrenched issues requires that we step up to take decisive action, to invite more of our fellow citizens to join in with the journey towards a better system, for food, farming and the countryside. At Sustain, we’re working to tackle these ideas head on as part of realisation of the UN Sustainable Development Goal – the Right to Food. This connects tackling food poverty with policies that also make sustainable farming (and fishing) (and natural resource management) a national priority, to secure good food and decent livelihoods for everyone.

So let us be bold and think big. Brexit is both daunting and disruptive. I sometimes feel it is a gigantic distraction from the more important things in life. But we do now need to look forwards. With so much in flux, and so many other priorities competing for our attention, it would be vain indeed to predict the outcomes. So let us simply invest our goodwill in cultivating hope and possibilities, and let us use the wonderful catalyst of better food, farming and a thriving countryside to do so. And if we can shift the system towards public goods; the money to invest in better things; and help more of our fellow citizens enjoy the benefits of good food, experience of tranquility and better health, you never know… we might even end up enjoying it.