A conversation between Simon Shaw, Food Power Programme Coordinator, and Ben Pearson, Food Power Involvement Officer

Simon Shaw: What is your approach to involvement of experts by experience? Are you trying something new or different?

Ben Pearson: I think often in the food poverty sector those with lived experience of food poverty are seen as ‘service users’ or ‘participants’. We are trying to embed a different approach so that individuals have meaningful roles as experts with strategic influence. Co-design and co-delivery are central to involving experts by experience, empowering them from the very start in designing the pilot projects to ensure the methodology and tools used are engaging for people. For example, young people have designed empowerment exchanges and delivered workshops to other children and young people on the issues they have identified and using the tools they enjoy. Asylum seekers and refugees in Luton will use food and eating together as a catalyst for conversation and storytelling. Young people and older people in rural Lancashire will co-design tools with Imagination Lancaster to allow them to listen to each other and then involve food producers. In Hull creative activities with parents and young children will capture their own experiences.

SS: What can be the benefits of involving experts by experience shape a response to food poverty?

BP: Without wishing to generalise I find that experts by experience are incredibly resilient, they know what’s worked and what hasn’t worked, understanding at a grassroots level the impact services and strategies have on their daily lives. It’s difficult, if not impossible, for those who haven’t lived through poverty to truly understand the emotions, both good and bad, that are experienced on a daily basis. These emotions will influence people’s decisions, where they will and won’t go for support and what they will and won’t eat. It’s also important to remember the assets, such as knowledge and skills that those living in food poverty have. Empowering individuals to share these at both a practical and strategic level is important.

SS: How have you overcome any challenges?

BP: The biggest challenge in involving experts has been around the language and terminology we use around food poverty. Many of those ‘living it’ don’t identify with it, they are ‘struggling’, ‘coping’, living like their parents and grandparents or in a community with many others in the same situation; it’s part of their daily lives. It’s important to remember these are all individuals; their identities aren’t defined by poverty. So when recruiting or working with those who could be involved as experts it’s choosing the right language, starting the conversation with food, not poverty and talking about access and affordability, the food people like and want to eat. It usually means working closely with partner organisations which have trusting relationships with people and can help to get them on board. It’s also important to be flexible; often the adversities people face means attending a meeting or event isn’t straightforward. Providing childcare and travel expenses can overcome some of these barriers, but also exploring other ways for people to communicate and contribute.

SS: How do you encourage people to participate when some may feel that they can’t make a difference?

BP: People will sometimes feel that they can’t make any significant impact on their own. I think it’s about identifying small changes they can make in their community to start with; this is often what people will most relate to or be most passionate about. It’s really important to feed back to people what difference their contribution has made to ensure that they appreciate this. Other benefits include meeting like-minded individuals with similar experiences, amplifying their voices and to feel it’s okay to challenge the decisions of professionals who may not have lived experience. People already involved have said how just by being identified as an expert in itself is empowering.

Ben Pearson in conversation with Gillian Beeley, Blackburn with Darwen Food Alliance

Ben Pearson: What value has involving those with lived experience of food poverty brought to Blackburn with Darwen Food Alliance?

Gillian Beeley: I think the involvement of the young people and observing their workshops has been really quite salutary on two levels. Firstly that they don’t necessarily recognise what food poverty is, and secondly they then don’t really see it applying to themselves. Because the young people are talking about it, it means that when they present at our food alliance meetings it has more resonance and its making people think more widely from just food parcels and crisis food. It’s really helped to inform where the priorities need to be, moving away from crisis food to actually cooking and eating, using food as a catalyst for building communities and improving family dynamics is really important. The challenge now is for me how something that in essence that started as a public health eat well strategy now gets converted into a whole range of activities that are community driven and will impact on the wellbeing of the communities in Blackburn with Darwen

BP: How will people with lived experience be increasingly involved in the alliance’s work?

GB: It will help us prioritise what the food plan should be about. I’m struggling at the moment calling it a food poverty action plan because it’s how you talk about poverty and the stigma attached, and so at the moment I’m calling it a good food plan, good food for all. I think involving those with lived experience will help us prioritise what we do, but more critically affect how we talk about it and how we deliver or encourage the development of community based responses to food poverty. I think it’s challenging when they don’t recognise what food poverty is. I think all of us need to be a bit more circumspect. Say for example we try not to talk about the holiday hunger programme in summer; its holiday nurture, because it’s more than just food. It’s about supporting families through those long holidays; food is the catalyst to bring them in.

BP: How will involving people help develop a preventative response to food poverty?

GB: I think by involving those with lived experience and understanding their stories, collecting those stories and converting those into issues that can be campaigned on with those that have the power to make a difference. So for example, it may be about not collecting council tax in one lump if you’ve missed two payments because you haven’t a hope of ever managing that. The more we understand, the more people we can get to talk about food poverty and poverty more generally, hopefully this will mean politically we are more aware and we will get rid of a lot of the stigma attached to food poverty. I think it’s a really big ask because when people are under pressure then food is just the fuel to keep them going and the good food bit tends to be the secondary consideration. By building communities maybe we can have an impact on individuals and those in family units by making food more than just calories to keep you going, but a means to live better.

Ben Pearson in conversation with Tia Clarke, an expert by experience from Blackburn with Darwen Food Alliance

Ben Pearson: What value do you think young people bring to tackling food poverty locally?

Tia Clarke: People are starting to listen more to what we have to say.

BP: Do you feel talking to people with lived experience of food poverty can result in better solutions to tackling it, and if so why?

TC: Because they know how it feels, they’re not just guessing and making assumptions of how it is. Some adults are condescending; [young people] just agree with them because they [adults] don’t really care. But this feels different, young people open up more to other young people.

BP: How do you think other young people across the UK could be involved?

TC: They need to be empowered, treated like an adult and taken seriously. Then just get involved as much as you can and don’t be afraid of giving your own opinions. Get people to listen to you and tell other people about it.

BP: Could you tell me about how you have been involved in Blackburn with Darwen? How do you feel these activities can help prevent food poverty before crisis?

TC: We’ve designed and run workshops called ‘empowerment exchanges’ with other young people, people who sometimes don’t understand food poverty. The things we do help them understand more and they share their own opinions, helping adults to understand. People are then more aware of what’s happening.

BP: What does ‘people power’ mean to you?

TC: Empowering people to speak about what they want.

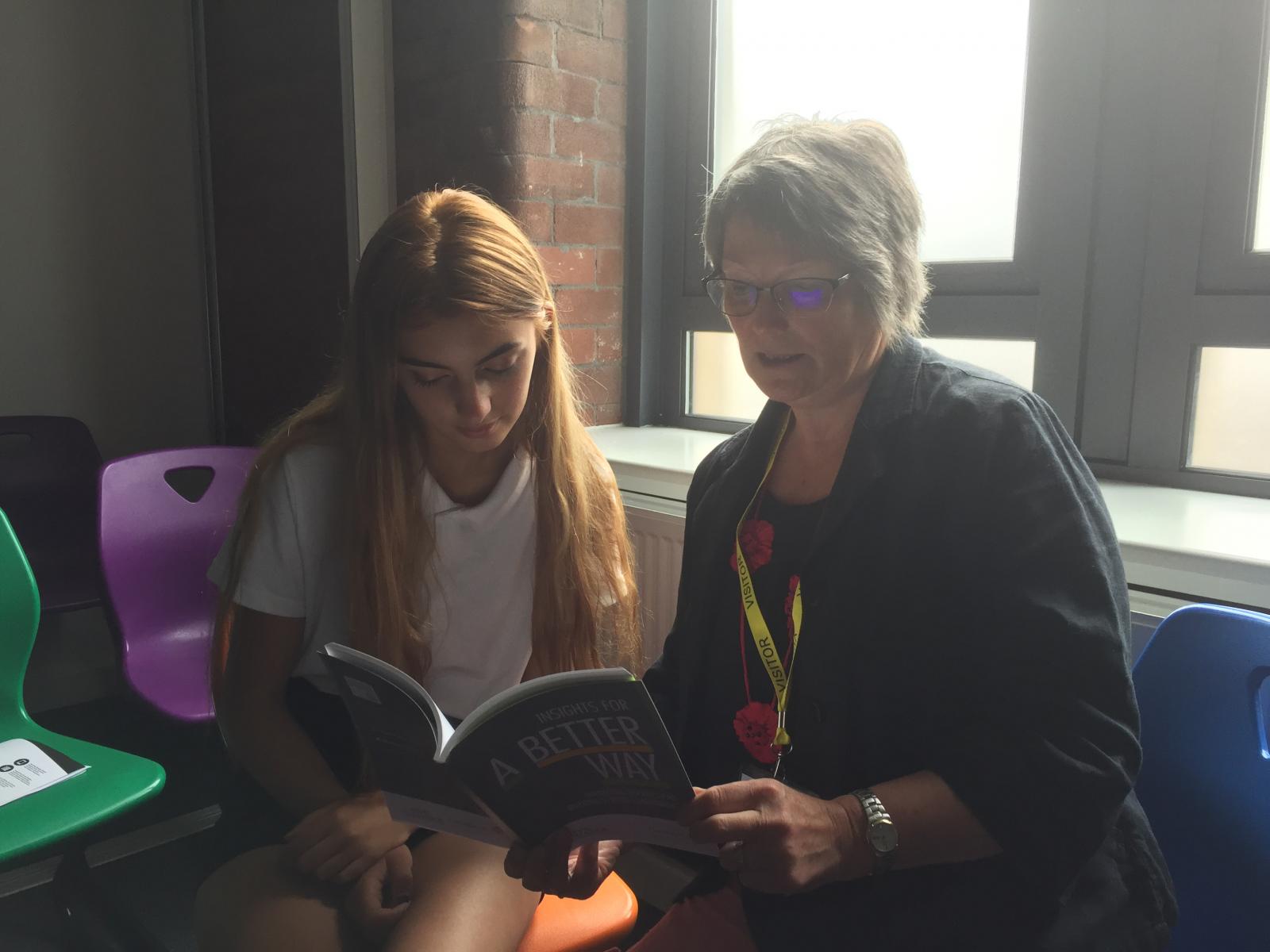

This article was first published in the A Better Way network's publication Insights for A Better Way: improving services and building strong communities.

Find out more about Food Power.